Why We Don't Know Our Needs

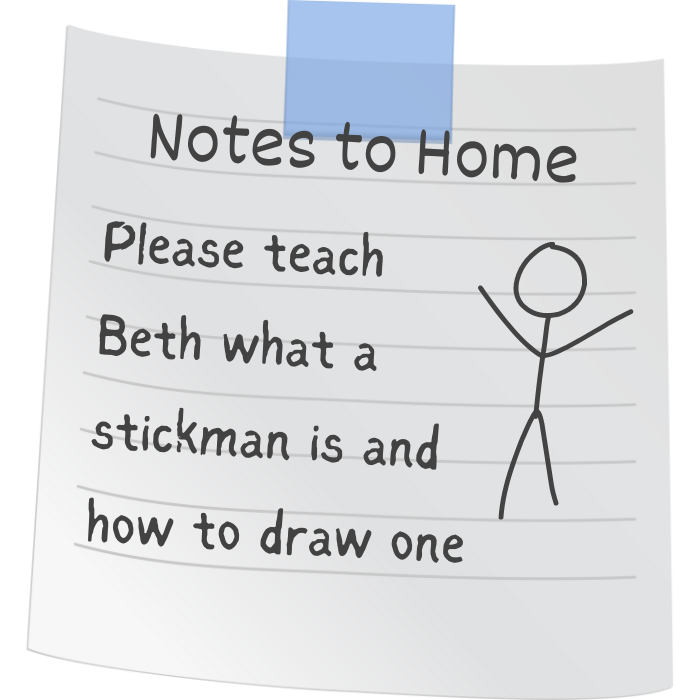

My teacher sent a note home on my first day of Kindergarten. She discovered I didn’t know some basics; like my last name, my phone number, my address, and most importantly, how to draw a stickman. My mom explained it was my August birthday…that most kids were older. This was part of my story through school where kids are compared to others the same school age. (Malcolm Gladwell’s research in Outliers explains the school year age gap issue.) Gladwell’s future insights aside, from that first day on, I’ve always felt like someone was going to send a note home with a list of things I should know.

I always felt clueless. It didn’t matter the subject, at home, school, or work. I learned to be quiet, never asked questions, waited for answers to be said out loud, and took advantage of being able to visually and audibly memorize whatever the teacher said. These were my core survival skills for the next five decades of my life. In fact I used them yesterday.

Not knowing ‘the right answers’ at home was confusing too. To be fair, my family was full of undiagnosed and untreated neurodiversity. I was the youngest of five and we were all building our ways to survive ‘not-knowing’ as kids. There were two unspoken rules: “Better to Remain Silent and Be Thought a Fool than to Speak and Remove All Doubt.” and “Don’t ask stupid questions, all questions are stupid.”

Beth, You Just Need to Apply Yourself

These rules were meant as protection out in the world, not to be cruel. They were helpful in elementary school, but not so much in the world beyond. Concern for my lackluster learning was replaced with “Beth, you’re a smart girl; apply yourself and be curious”. This unhelpful advice assumed I understood ‘apply yourself’, and I already knew that curiosity was bad.

When I went to university, Evelyn Wood Speed Reading Centers were in every strip mall. Reading faster made sense. It had to be the answer. If I could read faster, I would succeed. The sales rep at Evelyn Wood tallied my free assessment and said I needed remedial reading before I could learn to speed read. “Beth, I’m afraid you don’t have the reading ability to get into or complete college.” I told her I was already a junior in college. I was delighted with proof she was wrong,

I still felt lost even with this proof point. I rarely knew any answers in class or even when hanging out with friends. They used bigger words and they knew answers on demand. In my senior year, a professor walked by my desk during an exam to say “Beth, an angel from heaven isn’t going to come down to whisper the answer to you. You HAVE to FIGURE it out.” I had no idea what she meant.

What is Smart, Anyway?

Ultimately I decided being ‘smart’ was a key to success. Since I couldn’t be ‘smart’, I decided to be around smart people. I had smart friends. From them I learned to say smart things. I married smart people and I had smart kids. I worked for smart companies with engineers, lawyers, and other very smart people. Masking as a smart person by mimicking ‘smart language’ from one smart person, and repeating it to another smart person worked great.

The Problem with Masking

Camouflaging is an external behavior to not be visibly recognized as neurodiverse; and Masking is an internal process of noticing visible neurodiverse traits within oneself and concealing them. Camouflaging was an intentional survival technique for me, but not a thriving technique. My masking was unintentional. Both helped me blend in like a chameleon. This meant I could never be myself or see that I had needs. Learning to hide my issues made sense and felt safe. When I said, “Nobody thinks about MY needs.” The response was, “You’re right, we don’t. What are your needs?” I realized I didn’t know what my needs were. Was it my job to know? As a child, my parents looked after my needs, and I wasn’t allowed to question them, or ask for anything else. A lifetime of struggle started when I left home. I was now responsible for something I didn’t understand I needed. I focused on others’ needs in wistful hope they’d want to focus on mine. Because I never knew my needs, I unwittingly taught others they didn’t need to either.

Building the Foundation of Me

Becoming a whole person with self-esteem, agency and purpose is a lot of self-work. It means taking a break from your frenetic life of pleasing others to turn the focus uncomfortably towards yourself. At no point in my hectic life did I think pressing ⮚ Stop for self-exploration was a good idea. It would risk losing everyone I was busily serving. There was no room for Me since I didn’t learn self-work early in life. A structure for a ‘whole me’ was never built. Putting off the difficult self-work ended up risking everything anyway.

Fast forward a year, on New Year’s Day 2020, I sat in my airplane seat ready to spend the next 5 hours researching how to ‘find my values and needs’. It turns out it’s not about finding them; it’s about defining them. Setting values is the foundation to the whole-me effort. I worked through Pete Carroll’s and Michael Gervais’ Compete to Create book to build my personal philosophy as an internal decision compass. Vague concepts like setting goals and boundaries became part of my new skillset. Making decisions became easier as I measured every personal quandary against my new philosophy and value set.

Bring Your Values Work Home

Values work is both a personal and a family responsibility. It works best if our partner does the work too. When both partners’ philosophy and value sets are done, defining the couple’s set teaches us how to help our kids to create their own. Everyone can work together to create the family’s values set so everyone in the house lives from the same one. Homelife decisions become easier and there’s less friction. While you’re at it…check your career values against your personal values. Are they aligned? Are your team’s and company’s values aligned? Are they meeting your needs beyond financial? With your new values system, it’s easier to look within and “know” the answers. They’ve been there all along.

About the Author

The Latest in 'Ask Beth'

I’ve always gone out of my way to make others happy. I usually offer help and don’t wait for them to ask.

I’m in my late 40s and struggling with a new ADHD diagnosis. I’ve been messy and late most of my life, but I’ve also worked hard to make it up to everyone. Lately it seems I can’t get back on track no matter how hard I try, and it’s stressing me out.

No results available Reset filters?